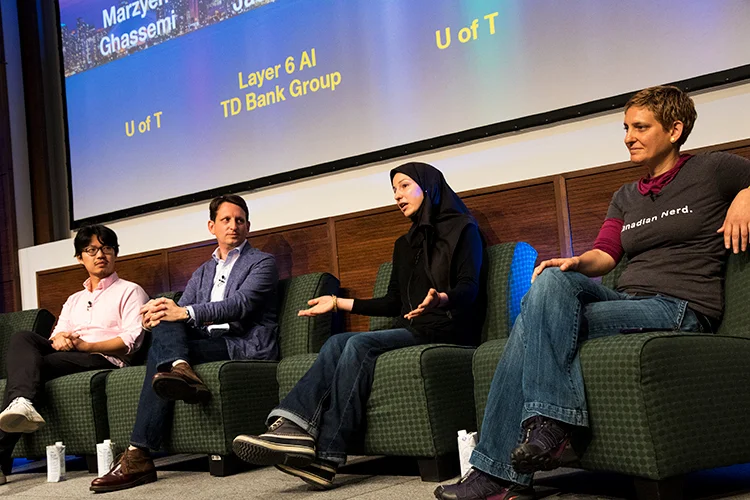

U of T Assistant Professor of computer science and medicine Marzyeh Ghassemi speaks on a panel discussion about AI. She is joined (from left to right) by U of T Assistant Professor of computer science Jimmy Ba, Layer 6 AI co-founder Jordan Jacobs, and Inmar Givoni, who completed her PhD in the department and is now a senior autonomy engineering manager at Uber (photo by Chris Sorensen)

Toronto’s tech boom – driven in part by artificial intelligence research at the University of Toronto – has prompted talk of a “Silicon Valley North.” But those actually ensconced in the Bay Area instead paint a picture of a research-driven innovation hub that’s collaborative, inclusive and uniquely Canadian.

At this year’s three-day Elevate technology “festival” in Toronto, Eric Schmidt, a Google board member and former CEO, lauded the way Canada’s post-secondary sector is being used to power the country’s innovation engine and said Canada should be home to “one or two” of the globally important companies that spring from the coming AI revolution.

“You have strong universities and the government is actually small enough, and sane enough, to help universities,” Schmidt told a packed auditorium at the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts minutes before former U.S. vice-president and climate change crusader Al Gore took the stage.

He added that Canada also benefits from close ties between post-secondary institutions and industry players.

Schmidt should know. The search engine juggernaut he used to oversee as executive chairman hired U of T University Professor Emeritus Geoffrey Hinton – known to many as the “godfather” of deep learning – and several of his graduate students to help lead its machine learning research efforts.

But Google didn’t just scoop up Toronto’s talent and split. It launched Google Brain Toronto and invested in the Vector Institute for Artificial Intelligence, a partnership between U of T, industry and the federal and provincial governments. Earlier this year, Google's sister company Sidewalk Labs also announced a partnership with Waterfront Toronto to design a mixed-use community on Toronto’s eastern waterfront that combines novel technologies and urban design concepts. Google also said it would be moving its Canadian headquarters to the new neighbourhood, known as Quayside.

“We chose Canada because it’s a good partner,” Schmidt said. “What happens when digital ecosystems thrive is there’s opportunities for everybody.”

The same collaborative spirit can be found at innovation centres like MaRS, which this week said it's leasing space at the Waterfront Innovation Centre in partnership with U of T. One of the world's largest urban innovation hubs, MaRS is a place where industry titans like Royal Bank and Samsung rub shoulders with top researchers from U of T and other universities, government agencies and dozens of promising startup companies.

That, in turn, has created a dynamic urban environment for innovation that’s attracting interest from around the world.

In the past month alone, ride-sharing giant Uber said it planned to pour $200 million into a new Toronto engineering lab, Microsoft said it would open a new office downtown and chip-maker Intel said it would set up an engineering lab north of the city that focuses on graphics processing units, or GPUs. That’s in addition to recent announcements by companies, from LG to Nvidia, to set up new AI-focused research labs in Toronto – all of which have a connection to U of T.

At the same time, a growing number of AI researchers have decided Toronto – and U of T – is an ideal place to do their cutting-edge work.

One of those people is Marzyeh Ghassemi. She joined U of T's departments of computer science and medicine [Faculty of Medicine] as an assistant professor this month after completing her PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and post-doctoral work at Google. Her research focuses on using machine learning algorithms to make better health-care decisions. Examples include predicting the length of hospital stays to determining when patients might need a blood transfusion.

Ghassemi said she was drawn to Toronto because of efforts like Vector, where she is also a researcher – a place where academia and industry are working together to support both applied and fundamental AI research.

“One of the things that was important to me when I was looking at very nice American schools and U of T was that freedom [to do fundamental research],” Ghassemi said during a panel discussion at an AI-focused Elevate event held at MaRS.

She added many U.S. schools place a big focus on commercial applications in the health-care space. “If the primary concern is how can we sell this, that can really stifle a lot of good research.”

Jimmy Ba, another new U of T assistant professor of computer science and Vector researcher, echoed Ghassemi’s comments and noted the quality of machine learning research being conducted at U of T and Vector now acts as a magnet for would-be students, including those who are already located near Silicon Valley.

“This year we had a lot of students coming from Stanford and Berkeley because the problems we’re working on here are more exciting,” said Ba, who did his PhD at U of T under Hinton.

Another key facet of the Toronto model are the arrangements worked out with many of Vector’s partner companies that allow top AI researchers to split their time between academia and industry. Such deals are viewed by many as key to retaining Canada's AI stars because they provide academics with an opportunity to take advantage of the significant salaries available to them in the private sector.

Jordan Jacobs, who co-founded Layer 6 AI (now owned by TD Bank) and Vector, cited the example of U of T Associate Professor Raquel Urtasun, an expert in computer vision and machine learning who who heads Uber’s self-driving vehicle lab in Toronto .

Without Vector, he said, there’s little doubt Toronto would have lost Urtasun and her students long ago.

“These are people who could have any AI job anywhere in the world.”

Prior to the panel discussion, Jacobs outlined his vision for how Canada can continue to capitalize on its early lead in AI – a technology he compared to electricity in global importance.

“Some countries are going to win and some countries are going to fall behind,” he said of the AI race. “We have the opportunity to be an exporter.”